- Home

- Betty Jane Hegerat

The Boy Page 13

The Boy Read online

Page 13

Every time I read the account of Cook’s trials leading up to his execution, I remembered all the bad movies I’d ever seen about men awaiting execution, final moments of redemption with weeping members of the family, the walk down the long corridor. Where, I wondered, were the lawyers in those last days? MacNaughton was the only one left now. Main was seriously ill by the time of the second trial, so his partner, Frank Dunne handled the defense. Both men died shortly after Cook was executed. But MacNaughton had had fifty years to carry this infamous case with him.

The online road report on December fifth said the route to Stettler was “fair,” a cautionary yellow line on the map. At 8:00 AM the temperature was zero degrees Celsius, and expected to climb to ten. Still, I threw my parka, boots, blanket, and a bucket of sand in the trunk. Filled a thermos with coffee. Tape recorder, notebook, pens, and the two books that stuck to me like barnacles, were in the canvas carry-all I’d begun to think of as my Cook bag. Did I need the books? They bristled with sticky notes, and were dog-eared, the spine on the Pecover book cracked so it fell open automatically to the photos in the centre. MacNaughton could probably tell me more than either of these two books. Take them, I thought. At least they show you’ve done some work already.

The CBC usually kept me company in the car. If I grew tired of radio talk on the drive to Stettler, the glove compartment held a pile of CDs, and I could switch to music. Or, I could enjoy the four hours of silence, but that was an invitation to Louise to wake up and I had now decided on a twist of plot for her story that I did not want to divulge until the words were on the page. I wanted the reins in my own hands. Louise had seized control like no other character I’d ever encountered, but I was determined that the ending to her story was going to be mine. Non-negotiable.

It was still rush hour at 9:00 AM, and traffic on the Deerfoot Trail came to a full stop so many times I was able to pour coffee and glance through my notes. Finally, beyond Airdrie the highway opened up. As the landscape flattened, a stiff wind whipped up from the ditches and threw a veil of white over the icy stretches. After a few miles, I relaxed. I am a good driver, and I enjoy the road.

I began to pay attention to the radio, to Shelagh Rogers on “Sounds Like Canada.” It was the eve of the eighteenth

anniversary of the Montreal massacre of fourteen young women at the École Polytechnic. Shelagh was interviewing two women involved in establishing monuments to the slain students in their respective cities. Both of them had faced fierce opposition and even personal threats. Ironic, considering their efforts were meant to honour the lives of women lost to violence. So much attention had been paid to Marc LePine, the man with the gun who’d killed himself in the end, one of the women said, that eighteen years later, everyone knew his name. But the names of the victims were lost. I turned off the radio.

Victims. Robert Raymond Cook’s name was part of Alberta lore, and his father’s by association, but many of the people I’d interviewed had forgotten Daisy’s name and no one but the man who’d been Gerry Cook’s best friend remembered those of the children.

I fumbled around in the glove compartment, randomly chose a CD and listened to the Rankin family for the next hour. By the time I got to Red Deer, the right-hand lane of the highway was snow-covered and it seemed no one else had noticed that it might be a good idea to adjust speed accordingly. I cut over on one of the secondary roads and hit ten miles of snow, an icy rut of tire tracks on each side of the road the only guide to staying out of the ditch, and those veered occasionally and then recovered the path. By the time I finally got to the intersection with Highway 21, I had begun to lose my driving nerve. Fortunately, the snow thinned, a weak sun poked through the clouds, the temperature rose, and there was so little traffic I drove for miles without seeing another car. Occasionally a truck sailed by, sending a sheet of brown slush over the windshield, slowing me to a crawl until the windshield wipers recovered the view.

I’d allowed an extra hour of driving time, and arrived in Stettler forty minutes early. The judge had given me directions to his home in the country and said it was only five minutes from town. I pulled into Tim Horton’s, emptied the dregs of my coffee in the snow beside the car and took the thermos inside. I’d had plenty of coffee, but I’d fill it up for the drive home. I knew I’d need the caffeine later. Over a bowl of soup, I watched people come and go. Almost everyone who walked through the door seemed to recognize someone else and the place was buzzing.

When I got back into the car, Louise’s presence was so strong she may as well have been sitting in the passenger seat. Apparently I had conjured her in that crowd of coffee drinkers.

Oh tell me about it. The joy of the small town coffee shop where you don’t need to worry about people overhearing your conversation, because they all know your business already.

The pretty prairie town I remembered from summer was bleak in its dirty coat of snow. The landmarks seemed to have disappeared and I drove in circles getting out to the northbound highway.

Lost in Stettler. And I’m counting on you to find our way to the end of this story?

Finally, I was out of town, and found the turn-off in minutes. I was to look for a sign that said “MacNaughton Ranch.” There was no missing it. The sign was big enough to declare itself even in the deep snow, the house was set on a rise, the driveway wide. I drove slowly up the snowy road and parked in front of a three car garage. Beyond the sprawling bungalow there was a smaller house set into a grove of trees. A collie resting beside the house got stiffly to her feet and shambled up to the door with me. It was opened within seconds by a man in casual slacks and a golf shirt who looked as though he could have been in his sixties. Right on time, said the judge, with a brisk nod, and I was glad I hadn’t lingered over a donut.

Women’s voices drifted up a staircase to the left of the entryway. His wife and daughter were making Christmas decorations downstairs with some other women, he said, and he ushered me around the corner into a living room that seemed designed for family gatherings. Two big groupings of comfortable-looking chairs and sofas and tables, a piano, and a window with a view to miles and miles of snow-covered prairie that in the summer would be a soft watercolour of greens and browns and big big sky. The judge sat across from me, a coffee table between us, his chair just a little higher than the sofa I was on, so that I found myself looking up to him.

This was beautiful property, I told him, a lovely home that felt like a good place to raise a family.

It had served their large family well. Five lawyers in the family, he told me with obvious pride. Two of his children had followed in his footsteps, two more had married lawyers. The smaller house out back had been his wife’s studio for years. She was a potter, but now that she’d retired from her craft, the studio had been renovated as a guest house.

We talked about the trip to Montreal, politics. He’d gone to support Stephane Dion in the leadership bid and was pleased to say the job was done. He’d been to many Liberal conventions, but this was one of the best. I asked if he’d grown up in this area, still wondering how Stettler had come to breed a Liberal. He was originally from Saskatchewan. Now that, I thought, helped to explain his political leanings. He’d come out here, he said with the hint of a smile, as a missionary. Actually he’d moved here in March of 1959 because he wanted a law practice that would leave him time for his family. He had five children by then and knew that a position in Edmonton, where he’d graduated from the University of Alberta, would mean long hours, high stress. It was the right move, he said, a good town.

I mentioned that Stettler seemed to have had more than its share of grisly crimes for such a peaceful looking corner of the country.

Again that bit of a smile. Some claimed it was the water, he said, and there had indeed been some “dandies.”

And then we were finally onto the topic of his first murder defense. He was an easy man to talk with. Warm and informal, in spi

te of his being perched just slightly higher than I. He watched and listened as though he was as curious about me as I was about him. He told the story as though he’d told it many times before. But, he qualified, it had been a while now. That same refrain I’d heard from everyone. It was so long ago.

The first Dave MacNaughton heard of Robert Raymond Cook was a phone call on Saturday night, June 27, 1959. Cook was being held at the Stettler police station and was trying to engage the services of MacNaughton’s associate who was not available. So by default, Dave MacNaughton took on what seemed to be a relatively simple case of false pretense charges. There was a problem about a new car, some unfinished paperwork, identification that belonged to Raymond Cook Sr., not the son who had picked up the 1959 Chevrolet Impala convertible in Edmonton. When MacNaughton visited Robert Cook in cells that evening, Cook told him that his dad was out of town but would be back in a few days and everything would be straightened out.

From all accounts, including Dave MacNaughton’s, there was no way to explain Cook’s return to Stettler as the actions of a guilty man. He drove up and down Main Street, showing off his new car. When he was asked to come into the station, he obligingly turned the car around and drove on down ahead of the police car.

At the station, he said he was sure his dad’s friend, Jim Hoskins, would post bail for him. Hoskins refused, saying he needed to talk with Ray Cook first. On Sunday morning, Dave MacNaughton had a phone call from the RCMP telling him he’d best come to the Cook residence before returning to his client.

Half the town was there, he said. They were taking out the bodies.

Dave MacNaughton went back to the cells with one of the RCMP officers. When they told Robert Cook his father was dead and they were charging him with murder, he broke down. It was claimed afterwards that he didn’t show much emotion, MacNaughton told me, but in fact, Cook broke down and cried.

Dave MacNaughton was two years fresh from law school when he met Bob Cook. He’d never handled a murder case, and he decided he wasn’t going to risk someone’s neck on his shortcomings. So he enlisted Giffard Main as senior counsel. Still, Cook ended up with his neck in the noose, MacNaughton mused. If he’d been tried a year later, he would have been sentenced to life imprisonment. He was the last man hanged in Alberta and only two others in Canada after him.

I remembered from Pecover’s book that one of Cook’s lawyers, MacNaughton, Main, Dunne, or perhaps all of them had said they couldn’t help but like Bob Cook. MacNaughton told me Cook was polite, respectful, all the way through from the preliminary hearing to the trials. After the first trial he thanked his lawyers even though he’d been found guilty. He couldn’t understand why the jury convicted him. He wrote a poem about it all. Dave MacNaughton said he had a copy of the poem. When he left the room to find it, I looked out at the snow. The sun was bright now, and the sky that milky blue of winter. I imagined walking the dog down to the mailbox. I had no idea if there was a mailbox but it seemed like a good thing to do on a winter day. I imagined children growing up here, building tree forts in the big grove of aspen I’d glimpsed as we’d passed the doorway to the family room and kitchen with large windows looking to the back of the property. I remembered that Clark Hoskins had built tree forts with Gerry Cook. I wondered if they’d ever ridden their bikes out of town and down this road. I remembered the large families, the small houses, and wondered if they had bikes. I wondered what Daisy Cook would have said about this house.

Then Dave MacNaughton was back, and pulled a faded photocopy from the file in his hand. I scanned the first page. Robert Raymond Cook was no great poet, but there was a sad poignancy to his attempt to convince the world of his innocence. Waiting for execution, he declared his serious doubt that there was such a thing as justice.

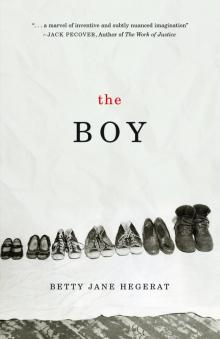

The file folder also contained newspaper clippings, one of them with a photo of a row of children’s shoes. One of the RCMP officers had lined the shoes up for the picture, MacNaughton said, and the prosecution tried to get the photo admitted as evidence. As if it was necessary to wring more sympathy out of this case. There were enough photos, MacNaughton said, that were positively horrific.

On the same newspaper page as the shoe photo there was mention of numerous confessions to the crime over the years. MacNaughton waved his hand dismissively. There had been confessions from England, from the United States. None of them at all possible, and a common occurrence in a “big murder” with wide publicity. The rumour most commonly cited locally was that Bob Cook’s uncle had confessed on his death bed. Nothing to that one either.

That brought us round to family. Did Robert Cook talk about his family, I asked. About his stepmother? Daisy?

Finally!

He talked about his dad, MacNaughton said. They seemed to have a good relationship. Dave MacNaughton hadn’t known Ray Cook at all, but knew one of his former employers very well. The father had a reputation for being light-fingered. Missing tools from the place of work, car parts, that sort of thing. MacNaughton said that when the white shirt found under the mattress turned out to be a mystery, he’d wondered if the answer was something as simple as Ray Cook having lifted it from a car he was fixing. And he just took it home because nobody had ever worn it.

The origin of that filthy white shirt hidden under the blood-soaked mattress, along with Robert Cook’s suit, had remained a missing piece of the puzzle. There were some other pieces of evidence that were never explained.

Yes, MacNaughton said, and those pieces had caused a lot of trouble. Bob claimed that when he came back to Stettler he dropped in at home, had a beer, picked up some suitcases his folks had left behind, and put them in the trunk of the car. But one of the police officers who’d stopped him in Camrose earlier that afternoon had searched the car, claimed there were already suitcases in the trunk. Yet another witness from Edmonton who’d ridden briefly with Bob Cook in the old station wagon before he traded it in said there had been no suitcases in that trunk. Who to believe? Bob just made things up as he went along, MacNaughton said. They all do.

Yes, they do. All of that legion of liars to which Danny belongs.

A merry band of men? Bob Cook told MacNaughton that he never robbed individuals. Just Treasury Branches. The lawyer had a twinkle in his eye, almost a note of admiration in his voice when he talked about this young man he’d defended. That same fondness that seemed to spill into all of the comments from people who’d known Robert Raymond Cook, from prison guards, to his jailmates, to the pastors who were with him at the end.

And such loyalty from his colleagues in crime. Jim Myhaluk was a good friend of Cook’s. He came to MacNaughton’s office after Cook was charged and asked what he could do or say to help. When MacNaughton pressed him as to what evidence he could offer, he said he’d come up with whatever would be best for his pal. Just tell him what to say. That’s the kind of guys they were, MacNaughton said. Whatever they could come up with to get him out of the jam.

Bob Cook, he said, had an answer for everything as quick as you could ask the questions. When he was captured after the escape from Ponoka, he told the police Myhaluk had helped him. MacNaughton discovered that Myhaluk had been in jail that night so he asked Cook what the real story was. Cook said that when he was in the lock-up at Ponoka, standing there at the window, he noticed that the bars moved a bit. The grout was loose. He just waited until it was dark, and he had no problem breaking out. And of course no problem getting a car started when he found one. His rationale for making up the story about Myhaluk? The police seemed to really want him to say that he had help. He told them what they wanted to hear.

On my trip to the Hanna cemetery, I’d wondered who stood there at the graves the day the seven were buried. Dave MacNaughton had no idea who’d arranged the funeral. He’d never spoken with anyone in the extended family. Not Ray Cook’s family, nor that of Josephine Cook, Robert’s mother. No one in the family came anywhere near Robert Raymond Cook after the

murders.

I’d been to the cemetery, I told him. And he, with a grin, said I probably didn’t find anyone there who could tell me anything. Bob had sent him on a wild goose chase through a cemetery too.

One of the unresolved pieces of evidence was around money Cook claimed to have dug up from a buried stash somewhere near Bowden—the loot, or swag, they called it variously in court—from the Vegreville Treasury Branch heist that had landed him in the Prince Albert penitentiary on his last incarceration. Cook told MacNaughton the can was still buried. If MacNaughton would just arrange a bit of a leave of absence he could take him there. To the exact spot. That, of course, was not remotely possible, so Cook supplied directions instead. MacNaughton said he went out with a shovel and the map, and ended up in a cemetery. He didn’t find the money.

He was quiet for a minute, waiting for me to ask another question, but I was still back in Hanna, staring at the stone on the grave. Thinking about the funeral.

Did Cook ask to see them? I was thinking out loud, I realized suddenly. Did he see their bodies?

Dave MacNaughton raised an eyebrow, that same twitch of a smile. No, he said quietly, not afterward anyway.

I sat up a little straighter.

He shifted slightly in his chair. Bob told them what they wanted to hear, he said. He could have taken a lie detector test and I’m sure he would have passed it.

About the escape from Ponoka?

That too. About any of it.

About the murders?

Yes. Because he didn’t believe he did it.

Do you? I asked.

He barely hesitated. Yes, he said. But he felt it was the same sort of situation he’d seen where someone had been raped or suffered some other brutal experience and then totally blotted it out of their mind. Cook had been in a fight with another prisoner just a few months before, and still had the scar on his forehead. He was a boxer in prison too. That was an angle MacNaughton said they followed. They thought the blow to his head in the prison brawl or the boxing matches might have caused brain damage. But Cook wouldn’t even consider an insanity plea. He didn’t do it. He wanted to take the stand.

The Boy

The Boy