- Home

- Betty Jane Hegerat

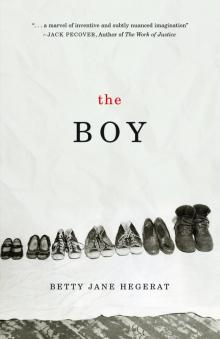

The Boy Page 17

The Boy Read online

Page 17

“Jake, it’s not gossip. Everybody knows where he is. We can’t make it out to be the fault of the kids. That’s what kids do. Lauren’s okay, I think. She’s way better at telling them to get lost and she’s the queen bee of grade one so the other kids want to be in her good books. It’s Jon who’s wounded every time.” Jon, she doesn’t say, who keeps trying to defend his brother.

Jake opens the bedroom door, words coming back to her over his shoulder. “Then it’s time he toughened up a little,” he says. “Don’t worry. I’m not going to tell him to duke it out. My pacifist upbringing is still too strong for that.”

What he does instead of talk, is to take both Jon and Lauren to the coffee shop for milkshakes, treat a couple of their friends as well, and make sure he tells everyone in the place that Dan is getting out soon, and he and Louise are optimistic. The boy has surely learned his lesson and it can only get better from here on in. Jon comes home with a smile on his face, swinging hands with his dad on the way up the front walk.

That night, spooned into the curl of her husband’s warm body, Louise keeps hearing the replay of the words he whispered before he fell asleep. “We have beautiful kids, Lou. So beautiful.”

She lies there, trying to feel reassured, feel everything right in her small world, and yet that cold hand clutching her stomach will not ease off. She shifts slightly, then widens the gap between them and finally slides away from Jake and out of bed.

After Jake stormed at her to get rid of Brenda’s Cook murder files, she stashed them in the laundry room in the basement in a box filled with quilt squares that belonged to her predecessor. Not that she had any intention of stitching together Brenda’s abandoned project, but the neat piles of colour and texture-coded squares seemed too precious to be thrown away.

The concrete floor is like chipped ice on her bare feet. She pulls a pair of Jake’s socks out of the dryer along with the sweatshirt he wore around the house on Sundays. When she’s warm again, and the creaking of the basement steps and all the other sounds of the old house that she stirred when she made her way down the stairs have settled into silence, she opens the scrapbook to a clipping from the Red Deer Advocate, July 3, 1996, the Cook case brought to light again because of the publication of Jack Pecover’s book.

Under the headline, “Did He Do It?” the newspaper article includes a collage of faded photos: Robert Raymond Cook’s RCMP mugshot; a snap of the five Cook children squinting into the sun; a formal portrait of a bespectacled Daisy looking every cell the school marm; the white frame bungalow with the truck parked next to the garage; and finally a crowd in the street in Bashaw waiting for a glimpse of Robert Cook after his capture following the Ponoka escape. Louise holds the photos close and looks hard into Daisy’s eyes. A serious face, but is she only imagining fear? She can’t bear to look into the children’s faces. She closes her eyes, leans her head against a garment bag of winter coats hanging on the wall and wills that scrapbook out of her hands, into the trash barrel, incinerated somewhere far away. Daniel Peters is Jake’s son, a boy she’s known since he was twelve years old, the brother of her own children. He is not Robert Raymond Cook. She is not Daisy Cook. There is no connection here. None.

Is that clear enough? Can we burn those clippings now? Donate the books to the next used book sale? I’m sure someone out there will find them morbidly fascinating. Can you tell I’m tired of this and I have a bad feeling about the way it’s going?

I’m not sure why. I know now how your story will end. You are not Daisy. But do we dare to imagine Daisy’s ending?

That’s the problem, isn’t it. Neither of us wants to go there?

You mean into the white bungalow on the night of Thursday, June 25, 1959?

Exactly. Why don’t you just write that story and cut mine loose?

Because no one knows what happened?

You’re a writer. Make it up.

I’ve tried. I can’t, because I don’t know the truth. And anything less dishonors these people.

But we can imagine it, to a point, can’t we.

Not me. Not even to a point. But I can give it to you.

All right then. This is how I’ve dreamed it.

Daisy, splashed by a blood-red setting sun, leans into the window. The air in the kitchen is soupy, not even the sigh of a breeze.

She lifts a corner of waxed paper covering the plate of sandwiches, pokes at a crust of bread. Mustard has dried marigold yellow on a protruding grey bologna tongue. She re-wraps, and presses the plate to the counter. Too late for the fridge? Lock the barn door when the horse is dead?

“Mommy?”

Kathy, cheeks flushed, kitty-cat pyjamas twisted, droops in the doorway between kitchen and bedrooms. Then Linda toddles to her sister’s side, blanket trailing, thumb corked between her lips. Daisy huffs the fringe of hair off her forehead. “Back to bed, babies!”

“Thirsty!” Kathy’s toes click on the linoleum. From the living room, the voices of her brothers are muzzled by the heat. “Bobby here?” she asks.

“Not yet.” Daisy scoops one pudgy girl onto each bare arm. She waltzes slow around the kitchen, sets the fly paper spinning. Then swoops over the grey arborite table. Linda’s diaper snags on the chrome edge. Daisy lifts, then bops her around the table, one damp print at each place. Deposits her finally on Daddy’s spot. Shifts Kathy to sit beside her baby sister. Lifting the corners of her apron, she fans a breeze for two flushed, up-turned faces. Reminds herself to take off the tatty apron. Berates herself that she cares. Touches her hair, self-consciously. Relives the plucking of a coarse strand of white from the red this morning. And feels that sting all over again.

From the living room, the opening music to 77 Sunset

Strip snaps its fingers. Daisy winks at Kathy. “Kookie, Kookie, lend me your comb!” she sings, tickles her fingers through the little girl’s hair. “Turn it down!” she calls to the boys. “Your dad will be here any minute.” Ray can’t stand the show. Kookie too much like Bobby, she thinks. So why isn’t Kookie in jail? And where is Ray? Where is Bobby, now that he’s been sprung?

Then loud voices in the garage, sharp as the edge of a shovel, the scuff of feet, the hard bark of a laugh, scrape of the door as it opens into the kitchen. Ray and Bobby, husband and stepson, drag the smell of grease and garbage into Daisy’s kitchen. She encircles the little girls, and calls the boys from the living room.

How am I doing? Is that you how you imagine it?

Yes. Almost exactly. And then …?

I can’t go any farther.

And neither can I.

Oh, I know that. You’re having even more of a problem going there than I am.

The Boy

After Louise burned the Cook files, after she agreed to take Daniel in once again, after Jake arranged to pick him up the day of his release, the boy disappeared. Jake phones from Bowden to say that the time Dan had given him for the pick-up was late by two hours. He was let out in time to get the morning bus to Edmonton. Jake’s going to drive on to Edmonton and check out a few possibilities.

“No,” Louise says. “Please don’t do that.” There’s such a long silence, she’s sure they’ve been disconnected.

“Why? I thought you were willing to take him back this time.”

“Don’t you get it?” she says. “If you go looking for him and coax him back home then he’s in control. Anything goes wrong, it was your fault for making him come back.”

Another silence. And then to Louise’s surprise, “You may be right. I’ll see you in a couple of hours.”

Jon, at the table doing his homework, doesn’t look up, and for a moment Louise thinks he must be was talking to himself. “If anything goes wrong if anything goes wrong if anything goes wrong it’s gonna be bad.” His voice winds tighter and tighter. “Mom?” eyes still focused on the map of Canada he’s colouring. “

Is Danny coming home with Dad?”

“No,” she says, and walks over to the table to look down at the neatly printed city names. Edmonton. Regina. Saskatoon. Winnipeg. In a few days Danny could be anywhere.

“Good,” her son says, so softly he’s an echo of the voice in her own mind.

The months with no trace of Danny are the most restful Louise can remember in the years since they moved to Valmer. People stop asking about him. In August, just a week before the collective birthday that seemed always to end in disarray, the phone rings on Sunday morning and it’s none other than dear old Alice. She asks for Jake, and Louise feels the familiar Dan-induced tightening of her jaw as she listens to Jake’s side of the conversation. When was he there, how long did he stay, did he say where he was going, how much did Alice give him?

After he hangs up the phone Jake stares out the window for at least a minute before he faces Louise. “Danny showed up at Alice’s a little while ago. Just out of the blue. She said he looked a little rough. She tried to get him to stay and eat with her, even spend the night, get a good rest, call me to pick him up.”

“What did he want?”

“He wouldn’t stay. There was a guy waiting for him outside.”

“What did he want from Alice, Jake? How much did she give him?”

“I think I’ll give Paul a shout and see if he’ll come to town with me. I’m going to check out some of Dan’s old haunts. Two can spread out and cover more territory.”

“If he wants to see you,” Louise speaks slowly, each word a labour, “he knows where to find you. He always has, Jake.”

“Are you saying I should ignore the fact that my son who’s been missing for six months turned up a half hour drive from here, and made contact with the one person he could be sure would phone me?”

“You think that’s why he went to Alice?”

“Of course. Why else would he go there?”

“Because she’s a vulnerable old lady and he needs money.”

“Jesus Christ, Louise!” He slams his fist down on the kitchen table, breakfast dishes flying, and Lauren, who appears around the corner from the living room at that very minute flies wailing to her bedroom. “Don’t you run to her!” Jake shouts at Louise. “She’s fine! It’s tears over everything and she’ll get over it in a minute.”

She stares at him. “Is this our fault? Mine and the kids? Go then. Track him down at one of the shelters, or maybe you’ll find him if you check every greasy coffee shop on the south side. Fortunately, it’s too early in the day for the bars to be open. And then you’ll bring him home? Shall I bake the birthday cake today instead of on Wednesday, just in case he takes off again by nightfall? Write welcome home on it?”

She can’t stop herself. “Daniel is not a little boy lost, Jake. The reason he hasn’t come home is that he knows what he needs to do to live here, and he’s not buying it.”

Jake grabs a kitchen chair and spins it around. He sinks onto the seat and leans on the back, his face in his hands. When he looks up at Louise she takes a sharp breath. His skin is chalk white, sweat beading his forehead. He opens his mouth to speak but all that comes out is a gasp, and then again he drops his head and slumps forward.

“Jon!” Louise wrenches the old phone from its cradle on the wall. 911? Out here, almost an hour away from ambulances, fire stations, hospitals? She doesn’t know who to call. Phyllis and Paul. Without pause, her fingers have already found those numbers but there is no answer. Of course not. It’s Sunday. They’re at church all day.

Jon, in the kitchen now, his head whipping back and forth, looking first at Louise who stands there pounding the phone into her hand, then at his dad who has managed to straighten up in the chair, still breathing hard but steadier now. “It’s okay,” Jake whispers, his hoarse voice stopping both of them where they stand. “I’m okay.”

But he is not. This Louise knows. Within minutes she has Jake in the back seat of the car, Jon next to him holding a cold towel to his dad’s face, his own pinched and tear-streaked. Lauren in the front passenger seat gibbering, “What, Mommy? What’s wrong? Where are we going?”

By the time they pull into the University Hospital Emergency entrance, Jake seems to be breathing a little more easily. But when the attendant asks him if wants to walk in, he shakes his head, squeezes Louise’s arm for a split-second and then transfers his weight to the man in the white coat who helps him into the wheelchair.

Three hours in the waiting room before Louise is called to the treatment area. But only she is allowed, not the children and she searches frantically around the crowded room, all those sick people, the coughing and the sagging bodies. Next to her, a young woman holding a listless toddler shrugs. “I’ll keep an eye on them for you, but who knows how long I’ll be here.”

Louise shakes her head. “It’s already too long for you,” she says. “You’ll be going in soon.” The nurse is standing there, waiting for her. “I can’t leave my kids alone. Please tell my husband that’s why I’m not with him. I’ll be there soon.” She’s been calling Phyllis since they arrived, but in a house that eschews technology there is no answering machine. Finally, on this desperate try, Paul answers. And yes, he says, they will be there within the hour. Hold on. Tell Jake to hold on, they’re coming. Again, she encircles Jon and Lauren with her arms. “Aunty Phyllis is on the way.” Meanwhile, she will feed her children. There must be a coffee shop close at hand. “Come,” she says, lifting them to stand with her. “Daddy’s going to be fine. I feel much better now. Let’s go find some food.”

Alone in her bed that night for the first time since she married Jake, Louise imagines him in the hospital bed. He is asleep, she’s sure, because when she leaned over to kiss him before she left, he struggled to open his eyes, the whites showing a tracework of red.

“He seems awfully weak, “she whispered to the nurse who was fussing with an IV pole.”

“Not bad,” she said. She put a hand on Louise’s shoulder. “Look at his lips. They look plump and pink as rosebuds compared to when we got him up here.”

More like undercooked liver, Louise thought, but the flesh on Jake’s face had settled into the familiar lines around his eyes, and the two vertical grooves over his nose on the high smooth forehead. She brushed back his hair, and grabbed a tiny piece of reassurance from the warmth of his skin.

“He’s groggy from the meds,” the nurse said. “We’ll keep him quiet for a few days and he’ll be back to you soon. You go on home now and get a good night yourself.”

How likely that she’ll ever have a good night again, she wonders now, the darkness in the room leaning a heavy hand on her chest. Jake laughed when they first moved here and Louise told him the house was too dark for sleep. Maybe they should use the bedroom at the front of the house even though it was smaller, she suggested, and she would leave the blinds rolled high so that the lone streetlight on the corner could dance a few shadows around the room. Maybe, he said, they could put on music for the dance as well. A CD of traffic sounds and noisy neighbours to really make her feel as though she was back in the city.

She finally relaxes, is slipping into sleep when she feels the tilt of the mattress beside her and warm breath on her cheek.

“Mom?”

She lifts the quilt so that Jon can slide in, then turns on her side. She pulls him close, breathing the funky smell of his hair. She sent the kids to bed without baths. “Can’t sleep?” She feels the back and forth of his thick hair on her throat. “Me neither,” she says. “I’m worried too.”

He pulls away slightly, his elbow caught in the neckline of her nightgown. “I heard noises,” he whispers. “Are you worried about Daddy?” She frees him from the fabric, his bones so small in her hand. “But he’s going to be okay, isn’t he?” Jon says, his voice croaky.

Jon’s breath is stale, garlicky. After Phyllis brought the kid

s home, she fed them a cheese and sausage snack while they waited at the living room window for Louise to arrive back from the hospital. They would not budge from that window, Phyllis told Louise when she phoned to say she was on the way.

“Yes of course.” She nods. “The nurse told me when I was leaving that Daddy needs a few good days of rest and he’ll be home.”

He sniffles and pulls a handful of sheet to wipe his nose.

“Go to sleep,” she says. “Things always look better in the morning. Honest.”

“It’s not Daddy I’m worried about,” he says. “It’s Danny. Why won’t he come home?” She sighs, too weary for this discussion. She cannot force herself to parrot Jake’s forced optimism, tell this little boy his brother is going through a bit of bad behaviour that some young people try out, that he’s going to grow up very soon. And he’ll have learned his lesson. And he’ll stay out of trouble for good.

“I don’t know,” she says. “No one except Daniel knows, and he’s not ready to tell us.” Jon is quiet, and for a minute she thinks he’s fallen asleep.

“I’m so scared,” he says, “cause Danny doesn’t have anyone looking after him. He could get hurt really bad.”

“Shhhhh,” she whispers. “Go to sleep.”

As his weight settles against her and he begins to snore softly, she thinks about Jake and what he would say if he walked into this scene. He would say that Jon is too old to be coming into their bed. That she’s coddling the children. She wonders if Brenda faced the same criticism, or if Daniel was a more independent, thick-skinned boy than this little brother of his. Daniel was only ten when his mom died, just two years older than Jon is now. She can’t imagine the boy in her arms motherless. Nor fatherless. She simply will not let her mind move in that direction. Not imagine herself alone forever in this creaky old house with her children.

By the time Louise feels her bones begin to settle into the warm sheets, she can see reassuring streaks of dawn around the edges of the blind, and sometime later, she’s pulled briefly out of a fretful dream by the sound of a car in the driveway. Then she’s back in the misty hospital corridor, running from room to room, looking for Jake.

The Boy

The Boy