- Home

- Betty Jane Hegerat

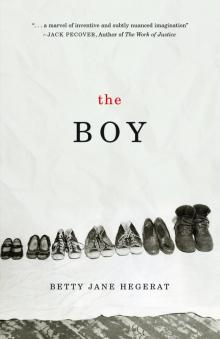

The Boy Page 3

The Boy Read online

Page 3

Roads Back

I didn’t go to Stettler immediately after dredging up the information about the Cook murders. I was tempted, but without a clear mission, without the remotest idea of what I intended to do with any of this horrific story, there seemed little point. Instead, I found myself returning in memory to the towns where I’d grown up. The summer of 1959, the summer of Robert Raymond Cook, returned with the memory of a girl who’d been one of my best friends in the year after we moved to Camrose from the much smaller town of New Sarepta thirty miles away. I had no recollection of how long that friendship lasted. No memory of Rose beyond elementary school, but I was as sure as I could be that it was Rose who told me about the Cook murders. I could hear her slight lisp, see wide brown eyes, high cheek bones, long brown hair.

Rose lived three blocks away. It impressed me so, at ten, to be living in a place that was measured in blocks, to have an address instead of a post office box. New Sarepta had no more than half a dozen streets when we lived there; a creamery, post office, service station, general store, church, school, and hotel. And a coffee shop, owned and operated by my parents. We had living quarters in the back, and my mom cooked and served meals, while my dad drove away early every morning to check well sites for Edmonton Pipeline. Oil pump jacks in farm fields were as much a part of the landscape as barns and fields of barley. The year before I was born, oil well Leduc Number #1, just twenty miles away from New Sarepta, “blew” and there were good paying jobs to be had for every able-bodied man around. And for men from away as well. Our small town had an unusual number of strangers passing through, and many of them passed through our door.

I was so shy about this business of feeding strangers that went on in our home, that I lurked at the side of the house rather than out front or inside where men’s dark green work shirts hunched like turtles over coffee mugs thick as bathroom sink porcelain. Their big bums spread on the red shiny stools where, after the coffee shop closed, a child could twirl until she was falling-down-dizzy.

Saturday night after closing, Mom would be on hands and knees doing a “proper” scrubbing, the pail of water emptied again and again. I can still evoke the smell of Johnson’s paste wax that clumped in our throats late into the evening, hear the rustle of sheets of newspaper spread over the thick wax until it dried. On Sunday night, my sister and I in thick grey socks skated under the blue fluorescent light until every dull patch was swirled to a high shine.

When I slipped through the front door into the shop with its long stretch of counter, I would see my mother’s permed head in the pass-through to the kitchen, apron straps crisscrossing the back of her dress, one elbow crooked over the pan of onions. When the special of the day was hot hamburger sandwiches, our house, clear to the bedrooms at the back, reeked of onions and grease.

We only moved thirty miles when we left New Sarepta and the coffee shop, but at ten, it was a world away to me, and a welcome one. No more strange men in our house, no more muddy streets.

Camrose had paved streets with numbers, parks, a movie theatre, library, and a social structure. Here my mother seemed to tag each of my friends with the occupation of the father. The banker’s daughter, the funeral director’s son, the school principal’s kids, the optometrist’s boy. But those like us, the working class, went untagged. When we moved to Camrose my mother worked as a seamstress at a dress shop, my dad still driving out to the oilfields. I never knew the occupation of Rose’s dad. She was the girl from the family of ten kids. That description eclipsed all else, even though large families were common then. The small, crowded house was the reason my mother gave for refusing permission for me to sleep over at Rose’s. She saw no reason for children to spend the night anywhere but in their own beds. My mother couldn’t imagine how all those children fit into a small bungalow, and she certainly wasn’t inflicting another on Rose’s beleaguered mother.

It wasn’t a slumber party Rose had on her mind when she pounded into our yard that day, Monday, June 30 when the news of the Cook murders broke. It was likely the last day of school. No early exits in those days. I imagine that Rose and I had hauled our bags of end-of-the-year grade five books and papers to our respective houses, that she reappeared just before suppertime, which at our house was the early hour of five o’clock, as soon as my dad walked through the door.

Memory tells me I was outside, sitting on the back step, pouting. Because my mother had refused another sleepover? Because I was prone to pouting and it was the surest way to irk my mother? In my memory, too, there is the smell of meat frying, my mother busy in the kitchen but keeping an eye on me through the open window, ready to come out and tell me that if I was sulking and bored already, she’d find some work to keep me busy. Boredom irked her even more than pouting.

Then Rose, wide-eyed, breathless, hair dangling around her ears from the ponytail that never lasted the day, racing along the cotoneaster hedge that separated our yard from the alley. Bringing the news. Dead bodies in a hole in the floor in a garage. Bodies of little children. This is the news I remember.

Rose would have heard it from one of her brothers. But her brothers were forever trying to scare her with creepy stories about graveyards and people buried alive and rats climbing into babies’ cribs and gnawing off their fingers and toes. We didn’t even have rats in Alberta and yet she believed them. So why would I believe a story about a pit full of bodies?

Because it was on the radio, she said, and Rose’s oldest brother knew the person who they said had done the awful

killing. Robert Raymond Cook. I can hear Rose pronouncing his name like she was broadcasting the news herself. All summer long we would hear him formally named.

No, I insisted, this couldn’t be true. Especially when she told me that he was the son, the brother of the dead children. I didn’t have brothers, just one older sister, but I did have a sense of what brothers would or wouldn’t do. Tease, torment, bully, but not murder. It must have been a stranger. If Stettler was anything like the small town we’d left behind, then a stranger was the answer.

My mother verified Rose’s story when she came outside to find out what we were quarrelling about. She had heard the news from Stettler, and if she had heard, it had to be true. It was not the sort of information she deemed suitable for eleven-year-old girls, though, and she sent Rose home. The radio that usually played during supper so my dad could hear the weather report was turned off. The Edmonton Journal disappeared the next evening as quickly as the paperboy dropped it on the front step. But Rose was my pipeline, and eventually we got the story in its ghastly entirety. The children had been “bludgeoned” to death. I got out the Miriam Webster for that one, and for “stench” which I heard my dad quietly ponder to my mother. My dad didn’t share my mom’s strict prohibitions on what we were allowed to hear. If my mom was out, or distracted, he would let us sneak into the living room and watch Alfred Hitchcock Presents. My mother was sure Hitchcock would plant the seeds of nightmare. Lassie, Ozzie and Harriet, those were shows suitable for children. If I could find my dad out in the garage, or in the basement, away from her keen ears, he would give me at least a censored version of the Cook story. Rose could be counted on to fill in the gore.

So, there were seven bodies, five children, the eldest a year younger than me. The son was a jailbird, just out of “the clink” my dad would have said, a few days before the killings. And if I asked how Robert Raymond Cook was captured, Rose might have described a car chase, with her brother in the lead, heading Cook off at the junction service station. My dad would probably have told me that they didn’t have to catch Cook. He was parked outside the coffee shop in downtown Stettler, showing off his new car.

It turned out Rose’s brother didn’t really know Robert Raymond Cook, except that he’d been at a party Cook crashed a year or two before. But what seemed to be accepted by everyone as truth from the moment the news hit the front page, was that Robert Raymond Cook “did it.”

Cook was sent to Ponoka, to the provincial mental hospital, for psychiatric examination before his trial. That was the second chapter in the story I had stored in my memory. For anybody growing up in Alberta, Ponoka was synonymous with craziness. It still is. Yesterday, from the window of this room, I heard my neighbour saying goodbye to a visitor. “I should be in Ponoka by now!” the woman said. Laughed and drove away, leaving me to wonder what was driving her mad.

If Cook was sent to Ponoka then, in my eleven-year-old mind, he was as crazy as could be. And guilty. Much of my memory of that summer is set on the three block stretch between my house and Rose’s. We must have trudged back and forth, whispering about murder, about brothers and boys. Though the Cook murders had dislodged it from our minds temporarily, another murder earlier in June had been centre stage. A girl in Ontario, exactly our age, out riding her bike, had never come home. Her body had been found in a field two days later, strangled, sexually assaulted. I didn’t need Miriam Webster for those words. At eleven, Rose and I were better informed about sex than we were about violence. A fourteen-year-old boy, Stephen Truscott, had already been charged with the murder of Lynne Harper when the Cook family was murdered.

It was officially summer, two lazy months during which Rose and I would have ventured out on the gravel roads around town, Cheez Whiz sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper and milk bottles full of Kool-Aid in the baskets on the front of our bikes. So long as we were back by suppertime, no one would have worried. But on July 10, Robert Raymond Cook broke out of Ponoka, and our wandering came to a quick halt. My mother didn’t need to place restrictions. Rose and I imagined a murderer, one with particular interest in children, hiding behind every tree, and even if we’d been allowed, we weren’t likely to wander farther than the playground within shouting distance of my house.

Even though he was captured three days later, the final chapter in my memory of Robert Raymond Cook, it seemed as though our summer-time freedom was irrevocably lost.

So this is your story now?

No. That’s as far as we need to go with my story.

Well you’re ignoring mine. And what about the Cooks?

What about them? They’ve been dead for forty-six years.

What happened to them?

I am not writing a story about bludgeoning and hanging.

Not that part. What happened before. Why did he kill them?

Why does it matter?

That’s the question, isn’t it? I knew you weren’t finished with them yet.

Roads Back

I found three books on the Cook case. The Robert Cook Murder Case, published by Gopher Books, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, was part of a series on infamous prairie murder cases by Frank W. Anderson. I ordered the book from a bookstore in Saskatoon, and tracked the other two books to the Calgary Public library which had one copy of each at the main branch.

They Were Hanged, by Alan Hustak, is an account of the last man executed in every province in Canada before the death penalty was eliminated in 1976. Photos of doomed men, one woman, introduce each chapter. Too much for me, I flipped to the picture of Robert Cook, the same image that must have accompanied the long ago newspaper articles because it was a match for the one that had been gaining focus in my mind since the drive to Longview. The Hustak account is short and sympathetic to Cook, I found to my surprise. Full of questions about the circumstantial nature of the evidence and political motives for denying the request for a commuted sentence. But at the end of it, another reader had penned, “They should have hanged Bob Cook ‘7’ times.” And he signed his note, “JD.”

The photo on the cover of The Work of Justice, The Trials of Robert Raymond Cook by J. Pecover was also familiar; a photo of a young man in suit jacket and tie, hair combed straight back, looking as though he could have been on his way to a school dance, or a first job interview. The book is four hundred and forty-nine pages, with two epigraphs:

“Who shall put his finger on the work of justice and say, ‘It is there.’ Justice is like the kingdom of God; it is not without us as a fact; it is within us as a great yearning.”

— George Elliott

“The whole case agianst me consists of suspision and if theres any justice in this world something will be done. However I am beginning to have serious doubts as to weither or not there is any such thing as justice.”

— “Letter from the death cell” Robert Raymond Cook

There is a foreword by Sheila Watson, author of The Double Hook, a novel which, I remembered with a jolt, opens with a man killing his mother. Even in the ten minutes I spent at a table in the library, skim reading, I found myself reaching for my pencil and the pad of post-it notes I carried in my bag. I put the pencil away. I would find my own copy for marking and defacing. Mr. Pecover, I decided, had a lot to tell me. The back cover said only: “Jack Pecover is a retired lawyer and an alumni member of the Canadian Rodeo Cowboys Association.” What I knew from the heft of this book was that Jack Pecover had spent a long time and a huge amount of energy examining the trials of Robert Raymond Cook.

An online search for the book led me to a used bookseller in Calgary. He would be at the Sunday morning flea market at the Hillhurst Sunnyside Community Centre, he told me in reply to my email.

There was one lone customer at the bookseller’s stall when I arrived on Sunday morning, a woman working her way through stacks of romance novels. In spite of the suffocating heat in the building, the man behind the table was wearing a heavy cardigan sweater. He seemed to be waiting for me; before I could speak, he dipped into a stash under the table and handed me the book.

I flipped to the publication date: 1996. This copy looked new, although the pages gave off the unmistakable musty smell of old book. I wondered who’d owned this, why they dumped it. I asked the seller if he’d had the book for long.

He shrugged, said it wasn’t exactly a hot number, but he’d sold a few copies in the past couple of years.

Then, I asked him if he remembered the murder case, a question I’d been posing to many people. He looked the right vintage. But he was from Quebec, he told me, where they have their own long list of bloody backwoods crime. Twenty bucks, he said, obviously not interested in chatting.

The romance woman, balancing her pile of books under her chin, wanted his attention. I pulled a twenty dollar bill out of my wallet and he snipped it up with two fingers and a wink.

All afternoon, I sat in the garden swing and read. By the time I reluctantly put the book aside, new images of Robert Raymond Cook had lifted off the pages; a boy barely able to peer over the steering wheel of a stolen car; the police chief in the village of Hanna, Alberta, in hot pursuit, muttering, that’s young Cook for sure. A boy who loved animals, and who was forever bringing home stray dogs. A boy who was markedly fond of younger children. A young man who carried photos of his five siblings and showed them proudly.

While I read, my sixteen year-old son and two of his friends were pounding out music in the basement. In a few minutes, they’d stomp up to the kitchen to chomp through a mountain of food before they moved to the basketball hoop. Goofy teenagers, with nothing more pressing on their minds than how to spend the rest of a sultry afternoon.

By the time Robert Raymond Cook was sixteen years old, he had graduated from reform school to big-time jail. His mother died when he was nine years old. In the solitary company of his mechanic father, he’d learned to drive by the time he was ten, and developed a passion for other people’s cars. From his first incarceration for car theft when he was fourteen years old, until his execution at twenty-three, he spent all but 243 days of 3247 days in prison. I imagined him, a young teenager, playing basketball in the exercise yard of the Lethbridge provincial jail.

I made the mistake of returning to the book later that night. At three in the morning, I was wide-eyed, grisly bits of information running in my head like

squirrels in cages.

The next day, I buried The Work of Justice under a pile of other books I’d set aside for summer reading. Anne Marie McDonald’s, The Way the Crow Flies, was at the top of the pile. I knew the book was about a murder, but it was fiction.

McDonald’s fiction threw me right back into 1959. Although The Way the Crow Flies is fiction, a novel, it seemed to me clearly informed by the Lynne Harper/Steven Truscott murder case. Once again, I was eleven years old, imagining a girl just my age riding into a summer afternoon on her bike, and never coming home again. I went back to the internet for information about Steven Truscott.

Fourteen year old Truscott was scheduled to be hanged for the murder of Lynne Harper two days before Robert Raymond Cook was sentenced to death. Truscott’s sentence was commuted. A similar plea for clemency was made on Cook’s behalf, and according to J. Pecover, author of my flea-market-found book, the odds seemed good. John Diefenbaker, who was Prime Minister at the time, was outspoken in his hatred of the death penalty. Unfortunately for Cook, there was an election looming and Diefenbaker was advised that he would lose the west if he showed clemency in a crime so heinous as the Cook murders.

I finished The Way the Crow Flies, satisfied in the end that it is a fictitious rendering. I knew all I needed to know about the Cook murders, and it was time to go back to Louise’s story. Fiction. I knew how to spin a story. Surely I could leave the Cook family to their rest.

Why are you so sure they’re at rest? If it were me…

It is not you, Louise. Danny is not a murderer.

How do we know this?

You know it because I’m telling you it’s so.

And if I don’t believe you? Maybe you’re wrong.

I’d like to remind you that I’m in charge here.

Ah, but you keep changing the story. Maybe Ray and Daisy Cook thought they knew Robert. Do you think they called him Robert? Why did the reporters always use his full name? So there would be no mistaking another Cook for the murderer?

The Boy

The Boy