- Home

- Betty Jane Hegerat

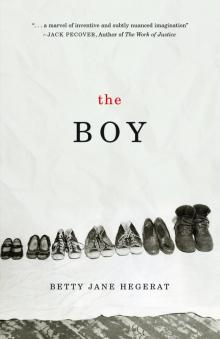

The Boy Page 5

The Boy Read online

Page 5

“What about Danny?” Jake asks. “Isn’t he worth at least giving it a try?”

Ah, yes, what about Danny? They’d planned to watch a movie together tonight, the three of them. Eat turkey sandwiches in front of the television. Maybe establish a new Boxing Day tradition, Louise had dared to dream. She’s pretty sure Daniel is not writing thank you notes in his room.

On a Saturday afternoon in late January, Louise rings the doorbell at her dad’s house, a courtesy she’s always followed, but finally uses her key when there is no sound of movement from within. Through kitchen, dining room, living room, she calls until she opens the bedroom door and finds him sprawled between bed and floor, one hand clawed for the quilt, the other clutching the telephone hand piece. There is no life in this pose, nor any doubt when she sees blood-swollen ankles protruding from striped pyjama bottoms. Still, Louise kneels beside her father, trying to warm his cold cheeks between her palms.

The exact time of his death, the medical examiner tells her, isn’t an easy thing to determine. This is not television or the movies. Some time between late evening and early morning Friday, most likely. What does it matter? Louise keeps trying to convince herself there was nothing she could have done to prevent this.

She realizes that she has been preparing for the death of her mother, assuming that she would struggle with a guilty mix of relief and sorrow, but she and her dad would cope, comfort one another. Now, numb and disoriented, she plods through the funeral arrangements and the small private service—just a handful of relatives and close friends—without shedding a tear.

The morning after the funeral, she wakes with a strange sense of urgency, swings her feet to the floor, but when she tries to stand, her legs collapse under her. Three times she tries, three times she falls back onto the pillows. Finally, she curls up in a tight ball and weeps. When she’s finally spent herself and is silent except for the rhythmic trembling exhalations of her breath, the bedroom door creaks open and she hears Danny’s hesitating footsteps approach the bed, then stop a few feet away. Jake left for work an hour ago, with a kiss and a promise to be home early.

“Louise?” Danny’s voice cracks on her name.

“It’s okay,” she whispers, throat raw from the sobbing. “I just feel sad because my dad died. I needed to cry, but I’ll be okay now.”

She pulls herself up on the pillows and looks at the boy. He seems so small at times, times like this, and at other times when he enters a room he seems to grow to fill the entire space, sucking up the air. She brushes the hair from her face and tries to smile. Her “flu” has been properly diagnosed. She’s pregnant, but she and Jake have agreed that it’s best to wait a bit before telling Danny.

“Should I make you tea?” he asks. “I always made tea for my mom when she cried.”

“That would be very nice, Danny.” She glances at the clock. “We’ll have a cup of tea, and then I’ll drive you to school.”

“Don’t you have to go to school?”

“No, I have a few days off because of my dad.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I have to go visit my mom.” There was no question of Louise’s mom attending the funeral. The big question is how to tell her that her beloved husband of almost fifty years has gone on without her. Louise has been looking forward to bringing her mother the news about the baby, sure that when she takes the wrinkled hand and places it on her belly, a light will go on. She planned to take her dad to the nursing home that day and tell the two of them together. As always, she waited too long. Surely it would have made a difference. Maybe a few extra heartbeats would have strengthened that muscle.

“Why tell her about your dad at all?” Jake asked. “What’s the point in trying to crack through that shell in order to make her sad?”

Louise would like to agree with Jake. It would be so much simpler that way. But when she sat down at the piano yesterday after all the funeral guests had finally eaten their egg salad sandwiches, drunk their one glass of wine, sipped a cup of coffee with a few nibbles from the avalanche of sweets that poured in from neighbours, she held the wedding photo in her hand and looked into her mother’s face. She would want to know. If she’d been given the dignity of voting on these matters before dementia moved in, she would have voted to know.

Self-conscious suddenly to be lying here, the rumpled nightgown twisted around her thighs, she pulls the quilt over her legs.

“Can I come with you?” he says.

“Where? To see my mom?”

He nods. Louise looks away to the frost-encrusted bedroom window, and imagines sitting beside her mother’s wheelchair, holding the claw-like hand. How does Danny fit into that picture? If she takes him along, she’ll have an excuse to tell, and then leave quickly. I have to get Danny to school now, she’ll say to her mom, kiss her forehead and walk away. She will, of course, alert someone on the staff that she’s broken this news, but she’s sure they will only glance at the woman slumped in the chair, nod, and then she and Dan will stride through the snow to the car.

“We’ll see,” she tells him. “Yes, tea would be nice.”

He turns and walks out of the bedroom. The hockey jersey, she realizes, has been on his body every day for a whole week. Even yesterday, when Jake was trying to coax Danny into changing into a button shirt and khakis, Louise held up her hand.

“It doesn’t matter a bit,” she said. “We don’t need to wear black. Let him wear the shirt.” But today? Today he is going to school and someone will surely notice that the boy smells bad.

She dresses, and braids her hair. In the kitchen the pot of tea is on the table with two mugs, a jar of honey, a piece of toast on a plate. The phone rings before she can thank Danny. Jake, checking to ask if she’s okay.

“Danny’s making breakfast,” she says. “I’m going to see Mom this morning, and he wants to come along. Okay with you if he misses an hour of school? I’ll write the note.”

There’s a pause. “Why would you want to take Danny? Surely it would be better to be alone with your mom.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she says. “I think the company might make it easier.”

“Louise, remember who we’re talking about here. I’m glad Danny came through with the cornflakes, or whatever, but he’s not predictable. What if he says something off- the-wall and upsets you?”

Across the kitchen, her stepson is hunched over a bowl of Honeynut Cheerios. He looks up at her, blank, milk dribbling down his chin.

“Maybe you’re right,” she says.

“I don’t imagine he’s going to be too disappointed, considering his reaction the other time we took him along.”

Louise doesn’t get a chance to concoct a complicated excuse as to why Daniel shouldn’t come with her. She’s barely past, “Your dad doesn’t think…” when he stands up and grabs his jacket from the back of the chair.

“No, wait,” she says, “I’ll give you a ride.”

“Drink your tea. See you later.” He slams the door behind him.

Off to a good start, aren’t we, Danny and I? Is that the way it went with Robert Cook and his stepmother?

There’s not much in the books about Daisy. She married Ray Cook, became Robert’s stepmother, had five children, wrote letters to Robert when he was in jail, sent yellow socks and a red tie for his release in June 1959, and died of a gunshot wound to her head. In her bed, apparently, and then her body was thrown into the hole in the garage floor with those of her husband and children. Enough?

No. That’s not about Daisy. That’s about Robert Cook.

How is it about Robert?

He killed her.

The more I read, the more I wonder if he did.

We don’t care about that. We care about Daisy.

Roads Back

She was a red-headed school teacher. I skimmed

the chapters in The Work of Justice that chronicle the crime, the arrest, the manhunt and the trials, to find the section on Daisy in the chapter Jack Pecover titles, “The Seven.” About Daisy, there’s a scant two pages, quotes from girlhood friends, a description of the frugal but tidy house the investigating police officers described. Discounting, of course, the mayhem of the night of June 25, 1959. One paragraph about the five children. But Pecover’s book is about the crime, and the process that sent Robert Raymond Cook to the gallows.

Who, I wondered, was there left to tell me about Daisy, about those five children who, had they lived, would now be middle-aged? From Jack Pecover’s sketch, the quotes from Daisy’s friends, there emerges the portrait of a vivacious woman, no great beauty, but full of fun, quick-witted, and irreverent. One of two daughters, Daisy grew up on a farm, went to school in Hanna, took piano lessons every Saturday, and after a year of Normal School, the old teacher training program, came back to teach in her hometown. Strict, and dedicated to her students. Remembered by some—undoubtedly little Bobby Cook among them—as the “crabby” Miss Gasper, fondly remembered by far more. A talented pianist, who as a teenager, snuck into the Catholic church in Hanna with a friend one afternoon, and played “Elmer’s Tune” on the church organ while the other girl tap-danced. A teenager who, because of a promise to her mother that she would stay out of the Hannah beer parlour, hitchhiked to Drumheller with her friend to get drunk for the first time on brandy. Daisy became a stepmother when she married the widower, Raymond Cook, in 1949, three years after his wife’s death. She’d been Robert’s teacher, knew the twelve-year-old boy she was inheriting, a boy who had already been in trouble with the law. She was twenty-seven years old. Ray Cook was forty-two.

Daisy, the red-haired schoolteacher, stepmother of Robert Raymond Cook. A woman with a wicked sense of humour. When her second son was born in 1951, Daisy sent a note to a friend: “Roses are red, violets are pink. Our little Kathy was born with a dink. So we named him Pat.”

Gerry in 1950, Patrick (Patty), in 1951, Christopher (Chrissy) in 1952, and in 1954 Daisy gave birth to her Kathy. Then Linda in 1956.

Daisy, mother of five children born in six years. A woman with a circle of friends who grieved the violent loss of their fun-loving friend. All of them, I knew, would be old women by now, but the memories Jack Pecover recorded in the 1980s were so poignant that I wanted to find someone, any one of them, and hear about Daisy from a human voice.

I searched directories, made phone calls, sent letters, and did not find a trace of any of the four women quoted in the Pecover book. Then, I stumbled on an obituary in the Calgary Herald. Clara Bihuniak, age 83, had passed away peacefully in Edmonton. I had been searching for Clara Behuniak, a woman Daisy’s age, someone in her early eighties. Too much coincidence, I thought, a name easily misspelled. I sent a letter to one of the sons of Clara Bihuniak listed in the obit. Four days later, a man called. Yes, his mother was Daisy Cook’s friend he said, but he was not the person with whom I needed to talk. Call his aunt, Marion Anderson, his mother’s sister, he said. She lived in Calgary.

I knew it wouldn’t be that difficult!

When I told Marion Anderson why I was calling, about my interest in the Cook family, she sighed. She was seven years younger than her sister, Clara. She didn’t really remember much about the Cook family, or about those times, and she was busy, her family having a yard sale at her house that weekend. She remembered going to a wiener roast to celebrate the end of school when Daisy was teaching, hearing Daisy play the piano. She remembered how committed Daisy was to her students. After Daisy was married and living in Stettler, Marion Anderson had stopped in to visit. Daisy had two little girls, Mrs. Anderson remembered. She seemed surprised when I mentioned the other three children, the three boys. Could I meet with her, I asked, and she hesitated. Call me next week, she said.

I hung up the phone thinking I might have mined as much information in that call as was possible. The people who had the closest connections to the Cook family seemed the most reluctant to talk about the past, while anyone who’d been a by-stander seemed to have no hesitation at all in speculating and sharing their memories. My brother-in-law, who was sixteen at the time, remembered being stopped at a roadblock when Cook was on the loose from Ponoka. He said just being stopped made him feel that he must be guilty of something. And he was. At sixteen, he didn’t have the category of licence to be driving the farm truck. No one took note. Another relative in Camrose, Pat, knew several people who’d partied with Cook during the brief times he was out of jail and around the area. She was mesmerized by the murder case, she said. On November 14, 1960, she stayed awake listening to her transistor radio until the news sometime after midnight reported that Cook had been hanged. She still wondered if the right man was executed. During the years I was to spend writing this story, Pat would often ask what new pieces I had found to fit into the puzzle.

By now I had newspaper clippings, notes from casual

conversations with people who had lived in the area in 1959, recorded interviews—some enlightening, many just recounting the same archived information I’d already found—and no idea how I was going to use any of the pieces. Or why I wanted to. I tried once again to separate Louise’s story from the Cook murder story, tried to use what I was gleaning about Daisy Cook to add some veracity to Louise’s fears, and yet I couldn’t find any real evidence that Daisy was frightened, or in fact—if those who so fervently maintained that Bobby Cook was innocent—that she had reason to be. For now, Daisy and Louise were entwined.

Some kind of sisterhood of stepmothers? If you’re thinking Daisy and I are members of the same chapter, I’m cancelling my membership!

You don’t get to vote. You’re fictional, remember?

Are you sure? Doesn’t Daisy feel like fiction too? All of this gets a little blurry sometimes, doesn’t it?

A week later I called Mrs. Anderson again, without much optimism that she would have more to add. And that was how it began. She had not, she said, been able to dredge up much memory at all of Daisy, but to my surprise she said that she had been phoning other long-ago residents of Hanna to ask them what they remembered. The same details came up over and over again: Daisy’s red hair, her gift for the piano, and the shock to the community when the news of the murders broke. Mrs. Anderson recalled her sisters going to dances with Daisy, knew that they were very fond of their fun-loving friend. Marion Anderson had left Hanna by 1959. She heard the news of the Cook murders on television and phoned her sisters who were both living in Calgary at the time. They were stunned, unable to believe such a thing could befall their friend. But, she said, life goes on, and it was long ago. I suggested meeting with her, but she declined, saying she didn’t think it would be worth my time, but she’d be happy to chat now if I had questions.

I asked if she remembered Robert Cook, and she did indeed, but only as a small boy. She and a friend often babysat Robert and his cousin, Garry Bell, when the two boys were about four or five years old. Marion remembered that she and her friend played with paper dolls—they were that young—while they sat awake. They were not allowed to sleep when they babysat, even though the boys were already in bed when they arrived. The parents often went to dances. Bobby and his cousin were pests when they were awake, knocking on the door at Marion’s house, pleading with the girls to play with them. She remembered the boys in the kitchen, watching her mother bake cookies. Bobby was a cute boy, she said, and she was surprised later to hear that he’d become a bit of a bully in Stettler, that he picked on other kids. She didn’t remember how Daisy dealt with her stepson. Marion had left home by the time Daisy married Ray Cook.

I read Clara Bihuniak’s comments to Marion from the Pecover book and she said this sounded exactly as she

remembered her sister talking about Daisy. And the comments of Mrs. Joe Reilly, who it turned out was Marion Anderson’s other sister, rang true. She was curious ab

out my interest. So was I, I was tempted to say. So was I. A friend had just told me she had no intention of ever buying this book if I was lucky enough to get it published. My interest repulsed her.

I told Marion Anderson that my quest was really on behalf of a character in a story I was writing. I remembered the murders from my own eleven-year-old perspective, but another story, a piece of fiction, seemed to be demanding that I try to find the family in this crime.

Don’t blame it on me.

The Boy

July, 1995

In the first months of her pregnancy, Louise didn’t have the energy to resist when Jake set out to find them the perfect house in Valmer. Right to the end of the school year, she was wracked with morning, afternoon, and best-part-of-the-evening nausea. When they moved at the end of June, she let Jake do the packing, most of her belongings still in their boxes anyway.

Although Jake insisted the move was for Danny, the boy was even less enthusiastic than Louise. He refused to help with any of the unpacking, wandering outside instead, sitting on the back step, staring at the wooden sidewalk that led to the garage. Or riding his bike up and down the street for an hour at a time, bouncing a basketball off the side of the house until the sound drove Louise mad. Or sometimes just disappearing, but leaving her with the feeling that he was hiding somewhere. Watching her.

The house, she has to admit, is charming. It was built as the parsonage for the Anglican church, but when there was no longer a priest the members of the dwindling congregation had gone to other towns to worship. For the past five years, the elderly widow of the last Anglican priest to serve the parish had lived rent-free in the house. When she was shipped off to a nursing home in Edmonton, Jake, as hometown boy, was given first bid on the house.

The Boy

The Boy