- Home

- Betty Jane Hegerat

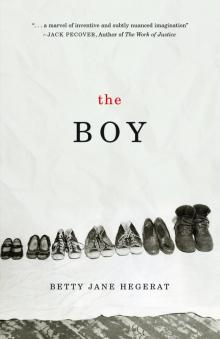

The Boy Page 9

The Boy Read online

Page 9

On the drive from Calgary, I’d been wrestling once again with my motivation for bothering this man, with my obsession with the Cook family and their demise. Every time I took off on a new tangent, I went through the same self-searching. What did I want from this? I was hoping that if I wrote about the crime, I might make sense of a young man raging through a home on a summer night and leaving

his father, stepmother, and five young children dead and battered beyond recognition. Sitting there with Clark Hoskins, it seemed an affront to decency to suggest that there was any sense to such an act.

Clark, though, had seemed interested and hospitable since he greeted me at the door. He’d put the coffee on and it burbled away behind us in the sparkling kitchen. I couldn’t help thinking of the contrast between this home and the humble house in the photos.

Outside, the fog that had almost kept me home earlier in the morning had begun to lift, and there was a promise of sunshine for the drive back. I’d considered going on to Stettler after talking to Clark. I’d been gathering names, scribbling them in my notebook. An astonishing number of people I knew seemed to have connections in Stettler; an elderly aunt or the father of an old friend who had lived there for years and remembered that summer of 1959 very well, I was assured. But I’d already discovered that the memories of the Cook murders had suffered the same fate as any other story. Each version offered a bit of embellishment, a new twist on Cook’s motive, or another theory as to who the real killer might have been. For now, I was confused enough with the conflicting opinions of the “experts” and it was probably best to leave any more wandering of the streets of Stettler until I had a real purpose. The little house at 5018 - 52nd St. was gone, an apartment building in its place. Present day Stettler had little to tell me about the Cook family, unless I could find the people who knew them.

We chatted, Clark and I, about weather, about the scorching heat to which he’d be returning in another week, and the dismal fall we were having here in Alberta, how the climate seemed to be changing. Or maybe, I thought,

our memories of the weather were just as susceptible to embellishment as all the other recollections. I’d remembered the summer of 1959 as oppressively hot. When I’d checked the national weather archives, their information said that on those days between the murders and discovery of the bodies, the daytime temperature averaged seventeen degrees with rain showers. In fact, the whole summer had been cool and wet.

For Clark, I was sure, it was a summer hung with cloud. He asked me who else I’d found, and how useful they’d been. He said he doubted much had been left unsaid. Nothing new to uncover. I told him it wasn’t the details of the murder case or Cook’s trials and execution I was examining, but what went before. It was the family I was interested in, someone who could give me insight into who Ray and Daisy were. I’d told him I was working on a book, one that might weave a fictional strand into the true story. I expected Louise to pipe up inside my head, but she was silent.

So far as anyone who knew the family—he shook his head. He thought his folks had known a few of the Cook’s “people,” but Ray and Daisy as far as he could recollect, had pretty much kept to their own. Someone in Ray’s family had looked after the funeral arrangements. He had no idea who they were.

His own family, he said, probably knew them best. Daisy and Ray Cook were the closest friends his mom and dad had at the time. The families went on picnics together. Gerry Cook had been Clark’s best friend. Clark had spent most of his “younger years” at the Cook’s house. Spent nights there. Staying with Gerry. He paused between sentences. In that house, he said, and paused again. A lot of time had gone by since those days.

When the phone rang and Clark excused himself to take the call, I picked up my copy of The Work of Justice. I wondered if Clark’s book opened by habit, as mine did, to the photos. If he’d visited, slept over with Gerry Cook, he may have spent a night on the “Winnipeg couch” in one of the pictures. I remembered these utilitarian pieces of furniture in many homes when I was growing up. Sturdily built of iron and coil springs, they were armless and backless and opened out to form a double bed. The striped mattress on the Winnipeg couch in the photo was blood-stained—blood-soaked, according to the book. The bedroom walls were splashed with blood. The three boys, Gerry, Chrissy and Patty had slept in this bedroom at the back of the house. It held a single bed, the double couch and two dressers. One of the other photos was a group shot of the five children taken one week before the murder. The youngest, Linda, was three years old. She was dressed in a striped t-shirt and overalls, and looking off to the side. I imagined her mother, smiling, telling her to stay put. Just for a minute. Five-year-old Kathy was beside her wearing a sleeveless shirt and a cherub grin. The three boys, Gerry, Chrissy and Patty, nine, eight, and seven years old, all had thick mops of hair neatly trimmed up the sides and wore identical short-sleeved button-up shirts. In another earlier photo on the same page, there were only the three boys; Chrissy just a baby, and Gerry and Patty, all of them wearing the fingerprint of their mother in the one neat curl on the tops of their heads.

I closed the book, and looked out the window into the thinning fog.

When Clark sat down again, he told me that his brother,

Dillon, would be a good person for me to speak with. Dillon was older and knew Robert Cook well. The only other person in the Hoskins family who could have told me more was their dad who’d passed away three years ago.

Jim and Leona Hoskins were the last people to see the Cooks alive. When they stopped by for coffee that Thursday night, when they planned the picnic for Sunday, Ray had offered to help Jim move some furniture on Saturday. When Ray didn’t appear, Jim went down to the Cook home and found the blinds drawn. There was no answer when he knocked on the door. The next morning, Bobby Cook called from the local jail asking Jim to post bail for him because there’d been some trouble over a car. Now Jim’s puzzlement over the family’s absence turned to real concern. He refused to help with bail.

It was Dillon who brought back the news that something bad, something very bad had happened at the Cook residence. He’d gone down to the house out of curiosity, and came home crying, this young man of twenty. There were yellow ribbons all around the place, he said, policemen everywhere. They’d shown him a bloody suit jacket. The one in which he’d seen Bobby Cook walk into town just a few days before. Oh yeah, Clark said, I can remember fully the day Dillon went down there and came back crying.

By evening, the Hoskinses knew the fate of their friends. Jim Hoskins was asked to go to the morgue and identify the bodies that night. And that, Clark said, was one of the things that truly did his dad in. One minute there’s a friend you talked to on Thursday night and the next minute … he couldn’t recognize any of them to identify them.

Clark looked down at the book, and so did I. A grainy photo of Robert Raymond Cook who seemed to be apprehensively watching something in the foreground. A flip of the cover would open my book to a black and white of the infamous grease pit in the garage, taken shortly after the layers of cardboard had been peeled away. There was a tangle of greasy rags, clothing, two visible faces, and protruding sets of hands. I avoided that photo.

Clark cleared his throat, and folded his hands on the table in front of him. You were asking me what kind of people they were, he said.

As I’d expected, he described ordinary folk. Ray, always working, always fixing, doing something around the place. A good provider for what he had. And Daisy. An ordinary good mother, who loved the children, no doubt about that. Welcomed other kids, made her house a comfortable place to be, but homework before playtime, always a teacher as well as a mom.

And the other son? Bobby, Clark had called him just a few minutes before, and I’d found myself trying to match that name to the newspaper photos and articles which referred to him always as Robert Raymond Cook. In the collection of photos in The Work of Justice, there is one of a much

younger Cook; a group shot of children, ranging in age from about five to nine years, I’d guess, labeled “Hanna birthday party.” Robert Raymond Cook, Bobby, is in the back row, oddly the only child formally dressed in a suit, white shirt and tie and looks a junior version of his neatly-suited self on the cover of J. Pecover’s book.

Bobby, Clark said, had seemed like an “okay kid.” He’d come along to a relative’s farm with the Hoskins family once when he was fresh from jail, and Clark’s mother had said that he was destined for trouble. Each time his son came home again, Ray Cook tried to get him a job, give him a new start, and each time he was back in jail again within weeks, it seemed.

Ray Cook had dreamed of owning a service station, and Robert Cook insisted the family was supposed to have left for British Columbia by bus on Friday morning to scout out a location where he and his dad could be partners in a business. He said he’d given Ray $4100 toward the purchase and Ray had left him the car to exchange for a new vehicle for himself.

They may have talked about a partnership, Clark said, and Bobby and Ray may have been serious, but the plan was certainly not in the works that weekend. Ray and Daisy would not have gone off without telling anyone their intent. Of that Jim and Leona Hoskins were sure. They were good neighbours, good friends, people with whom they spent hours playing cards, drinking coffee, sitting around the kitchen. They didn’t live “high class.” They had “the essentials” and that was it.

I imagined two women, two mothers with young families—Daisy with her five, Leona Hoskins with six children—sitting at the kitchen table in the modest Cook home, a pot of coffee on the stove. Daisy Cook was thirty-seven years old when she died. I wondered if she’d talked with Leona about the delinquent stepson. If anyone in the family talked about Bobby.

He embarrassed them, Clark said. In a small town, everyone knew what everyone else was up to. About 99% of the time Bobby wasn’t around, because he was in jail.

He tapped the cover of the book. And then Bobby came back, he said, wearing that blue suit. The Hoskins lived out on the highway back then, and Dillon saw Bobby walking into town that day around noon.

Clark said he was very sure that Bobby knew what he was going to do when he came home that day. That he’d had lots of time in jail to figure it out. He was going to fix them. He was going to get that car, and he was going to have some fun for a weekend.

One of the puzzling aspects of the story is that the family was killed sometime Thursday night or early Friday morning, and though Robert Cook had left Stettler that same night—the last time he saw them alive, he maintained until he died—he returned to Stettler after two days of joy-riding in the new car he bought in Edmonton with money he insisted he’d dug up from long ago heists. Then he cruised Main Street, and went back to the house.

Clark told me that while this seemed like bizarre behaviour for a guilty man, to him it was consistent with the rest of the luck Cook made for himself.

How, I wondered would someone plan the murder of seven people. One murderer and seven victims?

Yes, Clark agreed, the way he killed the kids did make you wonder if he had help. Five kids. Gerry was Clark’s age, just about to turn ten. And Chrissy not very much younger. And Patty. The girls were so small, but the boys? Active, energetic kids always running, building tree forts. Today, he said, kids are trained to phone 911, or to run for help. These were not stupid kids. That’s always been on his mind. How could someone beat five children to death with the butt of a gun, and not one of them get away?

The phone rang again, this time a cell phone on the kitchen counter and Clark rose to answer it. I busied myself jotting notes, but mostly pondering a nine-year-old boy remembering nights he spent in a bedroom that became the scene of unspeakable carnage.

I glanced at my watch. I’d taken more than the hour of Clark’s time that I’d requested. He was home for another week and then back to the Middle East for six weeks, a schedule he’d told me that would allow him to retire in a few more years. Then he and his wife were going south.

If someone had told him back when he was young that someday he’d go halfway around the world to make his living, he wouldn’t have believed it, he said when he came back. Yemen. Dubai. Far away in every way from the old house and his life in Stettler. He said he could remember frost on the nails in the walls in winter. Sitting by the kitchen stove, an old coal stove converted to gas, and when it was really cold the mattresses came out and everyone slept there on the floor. Hard times. Macaroni and tomatoes because there was no cheese. But everyone was fed, no one went hungry.

That was life in the Cook’s house as well. The house itself was boarded up for years, then finally moved a few blocks away and rebuilt. I wondered who would want to live in that house, knowing what had happened there.

We chatted another few minutes about the divided opinion on Cook’s guilt.

Bobby Cook left people feeling guilty, Clark said. In spite of his criminal record, and his lies, people warmed to him. The people who were there when he hanged shook his hand. They wept. They couldn’t imagine that a character like him could have committed such an act. Hard to imagine anyone who could do such a thing. Hard to fathom what could happen in one night to a family that was well and alive and playing.

The Boy

January, 1996

It’s Jonathan’s appointment for his six month check-up this afternoon, and Louise is trying to wash down a mouthful of soda cracker with flat ginger ale. This time the symptoms are familiar enough that she hasn’t wasted time speculating on the “flu.” She’s hoping she’ll be able to make the short drive to the public health unit without stopping to puke.

The outside thermometer showed minus forty-two this morning and she doesn’t have to bother converting. The two scales meet at minus forty and it’s bloody cold no matter how you measure it. The church budget didn’t cover any

upgraded insulating of this old parsonage; the window sills are furred with frost, and cold radiates from the outside walls. Louise worries every time Jake is ten minutes late

getting home from work. She imagines the car stalled on the highway, shrouded in ice fog, Jake’s cell phone dead because he never remembers to recharge it. What would she do without Jake? How did she go from being a self-reliant, capable city woman to a quaking, dependent wife for whom even the short winter drive to Edmonton has become a trial? Hormones, she tells herself firmly.

But then there is Danny. When the phone rings, she’s tempted to let the machine pick it up, sure the message will be another request from the school for her and Mr. Peters to come in and talk about Daniel. Jake has taken so much time off work for talks with the school principal and visits to the coffee shop and store where Dan has been caught swiping magazines and candy that he’s begun to worry about his job. It’s one thing to pop home in the middle of the day when you live in the same city, but an hour long commute turns the same errand into a three hour lunch break, and even with his seniority and sales record, the dealership is not pleased.

Maybe this time, Louise can deal with the problem, give Jake a well-deserved break. But when she picks up the phone, it’s Phyllis, and on impulse, Louise confides that she’s pregnant again.

“Oh my,” Phyllis says with her usual candor. “So close together.”

Louise has already decided that she won’t tell anyone this was an accident. She’d agreed with Jake who thought two children would be enough for this family, even though Jon will be as much an only child as Daniel has been. There’s Jake’s age to consider too. He’s ten years older than Louise, says he’s taken some ribbing at work already for being a new papa at fifty. Louise, though, is secretly delighted in spite of the prospect of puking for another eight months.

“Are you sick with this one?” Phyllis asks.

“All day long,” Louise says. “But it’s okay. Worth it in the end.” She won’t whine to Phyllis.

“Of course it is, but still I’ll send Marcy to you after school every day for a while so you can at least have a nap. We’ll let her have the car instead of taking the bus for a week or two.” Louise is sure Phyllis’s Marcy could easily run a household even though she’s just sixteen. Getting Daniel to clear the table and clean his room once a week involves more energy than Louise is willing to spend.

“It’s about time Daniel started doing some real helping around the house,” Phyllis says as though she’s reading Louise’s thoughts. “But for the love of God don’t let him babysit. Call me when you get home from the clinic.”

Louise puts the phone down and scoops Jonathan out of the playpen where he’s been cooing and trying to get his foot to his mouth. As if she would even consider leaving the baby with Daniel. Even Jake, she’s noticed, watches closely. One Sunday afternoon though, he came into the kitchen where Louise was cutting up a chicken for supper and beckoned to her with his finger on his lips.

They stood together in the doorway and peeked into the living room. Jon was on the sofa in his baby lounger, Dan beside him with a skateboarding magazine splayed open between them.

“Okay, now look at this one, Bro,” he said, “this is how it feels,” and with his hand as the board, he swooped past the baby’s nose, flipped, and came back to land on the terry cloth tummy of Jon’s sleeper. The baby crowed and waved his hands, feet pedaling, one of his rare smiles lifting his face in delight. The flip of a few more pages, and then Dan took Jon’s small fist in his hand and pressed it to the magazine. “See that one? That’s the one I’m going to buy for you when you’re big enough to skate, ‘kay? I’ll have a job, and my own place and you can stay over sometimes.”

When Louise turned to look at Jake, his eyes were clenched tight behind his glasses. She closed the door softly and put her arms around him, her face pressed to his chest. He took a deep breath and she could feel him nodding. “That’s the boy I want him to be, you know?”

The Boy

The Boy